The Night I Drove Home With A Dead Child In The Back Seat And What Happened Next

How a series of catastrophes I witnessed have shaped my choices as a journalist, up to and including making an enemy out of the U.S. Goverment, and why Anthony Blinken is a supreme wanker.

Flat 2, 58 Jagunmolu Street, Bariga, Lagos.

That was my address back in 2018, when I was a fresh-faced 28 year-old finally making a name for myself in the media and journalism spaces I had always dreamed of breaking into. At the time, I was a writer on Channels TV’s hit political satire show The Other News, and I was apparently quite good at it. So good in fact that, the US State Department had just nominated me for a spot on the Edward Murrow Program for Journalists under the 2019 International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP). My work had even been featured in the New Yorker magazine, and despite still being almost completely anonymous in Nigeria, I could tell that my big career break was coming.

At the time, I had what I considered to be a decent middle-class lifestyle in Lagos. I drove a 2009 Kia Rio that was my university graduation gift, and my missus and I - while hardly millionaires - pulled in enough monthly income to do pretty much everything a couple of 20-somethings in Lagos could aspire to do on a modest budget. In our apartment building at No 58, we were by far the youngest of 5 married couples, and we were the subjects of many an envious glance when we would regularly pull in to the house and offload multiple yellow Shoprite bags from the car, back in the halcyon days when N30,000 could fill a multitude of those bags.

The occupants of the other 4 apartments largely kept to themselves, but there was a particular guy that lived with his family in the BQ downstairs, who became something of a problem neighbour. The whole building shared one postpaid meter, and when the NEPA/PHCN/WhateverTheHeckTheyCallIt bill came, he would always pay his share late or sometimes not at all. When the water pump broke, which was often, he would not pay his share to fix it.

He would not pay his share for the weekly garbage disposal. Almost invariably, my missus and I - the only childless couple in the building - were expected to cover for him, after all we had no kids and we spent all our money on Saturday evening jaunts to Spur Restaurant and yellow Shoprite bags filled with groceries, because we were too good to shop at Bariga market like normal people.

He and his wife had 3 children of their own, plus a child from his wife’s extended family living with them. One of his 3 kids was a little boy named Korede. Korede was about 8 years old, but he had developmental problems and was very sickly. I never had the courage to ask what his specific learning difficulties were, but I did know that he could not use words and he was rarely seen without his mom lurking nearby, ready to give him a new dose of medicine or change his diaper.

On at least one occasion, I came home to find a suspiciously child-sized turd at the bottom of the staircase to my apartment. The kid was clearly in pain a lot of the time, and it wasn’t hard to tell how much of an emotional toll it took on his two siblings and his parents – an electrician and a petty trader – who were clearly just getting by. Because of Korede and the obvious struggle his parents were going through, I would often quietly cover the unpaid portion of the electricity and household bills. It’s not that I was such a good person - I just felt really, really sorry for this kid.

Sometimes when he was less sickly and in something approaching normal childlike health, you could sometimes see him make his way up our staircase, stretching his lean frame and trying unsuccessfully to peek into our house through the living room window. The world he was familiar with must have made us seem like aliens from outer space to him, and he would sometimes be found sitting for hours at the bottom of our staircase, staring longingly at our living room window like it was a portal to another universe.

Until one day…

“KOREDE OOOO!!!!!”

It was a late night in February when I heard a loud, frantic knock on the door. It was the neighbour in the flat directly beneath ours asking me to help rush the kid to the hospital with my car. Korede’s mom had apparently come back from running an errand to find him lying in an unresposive, non-breathing state. His siblings had apparently thought he was merely sleeping. Wearing only a jalabia and a pair of slippers, I grabbed my keys and ran to the car. Korede’s dad went in the front seat, and 2 of the other male neighbours squeezed into the back seat sandwiching Korede’s mom who was holding his limp frame and wailing piteously:

KOREDE!!! KOREDE EJOOO!!! KOREDE OOOO!!! KOREDE OOOOO!!!!

It sounded like something out of a Mount Zion movie, and it was one of the most terrifying sounds I had ever heard. I floored it to R. Jolad Hospital a few hundred metres away, with Korede’s screaming mom entreating the limp 8 year-old in her arms to wake up. When we got there, his parents went into the ER with the doctor while the remaining 3 of us waited in the reception. The other 2 men began praying to God to save Korede’s life. Atheist that I am, I was not much use and I just sort of stood around clearing my throat and feeling very uncomfortable. Over the course of the prior 9 months, I had witnessed my dad, then my father-in-law die in front of me. But nothing compared to the unique experience of witnessing a child facing death. It felt as if the air had a bitter taste.

Then came a sound that rent the air in the waiting room.

“KOREDE!!! KOREDE!!!!! KINI MO ṢE FUN Ẹ!!!! KOREDE!!!!! KOREDE OOOOO!!!!”

There was no solemn-lipped doctor walking out to tell us the terrible news, nor did we need one. Instead, the terrifying wailing got progressively louder, and the hospital reception got progressively quieter as Korede’s distraught mom emerged from the ER with her husband, cradling the dead 8 year-old boy in her arms. I looked around briefly and realised that nobody in the reception had the courage to look at the tiny corpse. Everyone else was making the sign of the Cross or going “Astaghfirullah!” All I could offer was a silent expletive under my breath as I gawked at the horrible spectacle.

“Fuck!”

A doctor who had followed them out of the ER broke our horrible silence with the world’s most uncomfortable “Ahem-hem.” He began quietly murmuring something about how the hospital couldn’t accept the body after confirming the boy was dead because they did not know the cause of death, and for legal reasons they’d need to do an autopsy, because the police bla bla bla. Honestly, it was an academic point - Korede’s parents couldn’t possibly afford to pay the mortuary fees at a private hospital anyway. We found ourselves walking back to the car because apparently, we were going home so the boy’s parents could decide what to do with his body.

And thus proceeded the most unpleasant 2-minute drive of my life - an impossibly grim journey back to No. 58 with a dead child in the arms of his wailing mother in the back seat. Being Muslims, Korede’s parents decided to bury him at sunrise at Yaba Cemetery, and they got back to the house shortly before 8AM. I had a day off work at Channels TV, so I decided to drop in around 9AM to offer some words of condolence. Amid the grimness, I kept an eye out for Korede’s dad hoping to offer a few words of encouragement to him in private but I did not see him there. I asked where he was and I had to stifle the shocked gasp that nearly escaped when they told me.

Korede’s dad had gone to work!

The Banality Of Disaster - My Introduction To The Wild

This was of course, not my first time encountering the ugliness that comes with disaster in Nigeria. I could vividly remember the ambulance driver telling me “We don’t carry dead bodies” and leaving my dad’s corpse on the living room floor at my family home just 8 months before this.

A few months after that, I would get to witness my father-in-law’s dead body stuck in the ambulance at Island General Hospital for over an hour with his uncovered legs sticking out of the back of the ambulance like 2 hefty matchsticks, either because there was not enough morgue space, or because nobody could simply be arsed to process the new entrant. It was Nigeria so nobody knew why, and nobody offered any explanation. If you didn’t like it, well, so what?

Korede’s death however, really got to me. It got to me because I realised that in Nigeria - the real Nigeria I now lived in, not the cossetted, Ogudu GRA version of it I once called home - not even the death of your learning-impaired lastborn child was enough reason to take even one day off from your desperate struggle to survive and provide for your family.

Korede might be dead, but his siblings and their mother still needed to be fed, clothed and housed. Korede’s dad was an electrician and he had to work whenever work was available - which was not all the time - or else the rest of the family would join Korede. To my eyes, it was a life-changing disaster. To him, it was Thursday.

When I eventually ran into him early in the morning a few days later and I launched into the heartfelt condolences I had rehearsed, he cut me off rather matter-of-factly with a response in Yoruba that roughly translated to “That boy suffered too much. God called him to rest finally,” and then he continued on his way.

He was going to work again.

Even worse, I began to notice a similar pattern of casual ugliness everywhere around me. Sometime later that year during the rainy season, a terrible story emerged of a young graduate trainee who got caught in a flash flood on her way back from work during a rainstorm in Lagos. Her drowned corpse was later discovered half-buried under debris inside a blocked drainage channel.

That’s it. That’s the end of the story.

Somebody’s daughter, sister, cousin, girlfriend, and colleague had done all the things she was supposed to do in life - gone to school, got good grades, graduated, done her NYSC year, got a good job - and how her story ended was that some rain fell one day and she randomly died. That was it. Gone. Forgotten. Except for this random guy on Substack writing about her in 2024 and her family, she was completely forgotten. That was it.

That was it?

In hindsight, it is no coincidence that 2018 turned out to be the year of my complete radicalisation. After 20-something years cocooned away in the comfort of Ogudu GRA and the UK, I had finally emerged into the country that I had returned to in 2013 convinced of the inevitability of ‘Africa Rising’ and consumed with the pursuit of my urban Nigerian middle class dream. I had reached what some would consider to be the zenith of the profession I was in. When you’re getting featured in the New Yorker, collecting IVLP nominations and appearing in Netflix documentaries, the next available step for a creative was to apply for a scholarship somewhere across the Atlantic and develop your career somewhere you actually had a chance to grow.

For me however, this crossroads in my personal and profesisonal life was where I chose to turn left instead of right. I looked at the country and society around me and felt 2 overriding feelings - bitterness and dissatisfaction. It wasn’t meant to be like this. Nigeria wasn’t supposed to implode in front of my eyes. Right in front of me, every dream and expectation I had once had of the Nigeria that would exist in my best years was going up in smoke. The military modernisation and Chinese-funded infrastructure megaprojects around the country that I once breathlessly followed on Beegeagles Blog and the SkyscraperCity Nigeria country forum were all severely slowed down or halted. Most of my friends from school whom I had attended university abroad and returned to Nigeria with had started moving to Canada, Australia, Germany and the UK. The word ‘Jakpa’ had become a thing.

Just 3 years before, the country I lived in was considered part of a new development bloc known as MINT - Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey. The burgeoning $510 billion economy - by far Africa’s largest at the time - was expanding at 7 percent annually and was forecasted to become the continent’s first trillion dollar economy by 2024. This wasn’t just airy-fairy talk either - the green shoots of technical transfer and actual industrialisation were starting to manifest. The Dangote Group had announced that it was building a 650,000 bpd oil refinery - the world’s largest single-train refinery - in Lagos.

A comprehensive nationwide rail masterplan had been drawn up and track-laying on the Abuja - Kaduna segment of the new national Standard Gauge network had already concluded. Lagos and Abuja had both kicked off construction on metro rail projects, and even though it appeared wrongheaded and doomed for failure, Port Harcourt appeared to be at least trying to do something roughly similar. China had kicked off its Belt-and-Road Initiative with Nigeria front-and-centre of its African infrastructure investment strategy, and it looked for all the world, like Nigeria was on its way to becoming an African economic behemoth. ‘Africa Rising’ wasn’t just a story - it was a manifest and obvious reality.

There was an indigenous vehicle manufacturer that had opened in Nnewi and begun pushing out more than 7,000 units annually using Chinese technology and IP. An estimated 65 percent of the value adding process happened in-country, with the electronics, plastic components, rubber components, frames, and batteries manufactured within a 100KM radius of the Nnewi factory. The Nigerian Air Force was preparing an order of 40 JF-17 Thunder jet fighters from Pakistan, with a local assembly facility for the aircraft included in the deal. Nigeria in 2015 was not quite on the cusp of a China-1979-type economic breakout, but an economic breakout was happening.

In fact I had come within a hair’s breath of personally benefitting from this economic updraft. Back then, I had applied for a helicopter cadet pilot program and after finding my way past 6,000 applicants and 4 gruelling stages of recruitment including an incredibly difficult WOMBAT test, I had earned a spot among the chosen 12. We were invited for a psychometric evaluation and the statutory NCAA medical examination at Kupa Medical Centre, then we waited for our trip to Bristow Academy in Titusville, Florida.

It never came.

A pestilence by the name of Muhamadu Buhari had become president, and - for some reason - that meant that the helicopter transport company responsible for the cadet program lost its transport contracts and soon went out of business altogether. The JF-17 deal vanished into thin air. The 650,000 bpd refinery was still struggling to make it off the drawing board. The rail construction projects had all stalled and Nigeria no longer seemed to be in any particular hurry to make use of the gigantic opportunity that was the Chinese BRI.

Back in 2015, even though I had worked in the Marketing industry and I had a front row seat where I witnessed the shenanigans involved in Mr. Buhari’s electoral campaign, I did not yet grasp the full ugliness of what was happening to Nigeria, nor did I completely understand how it would play out over the coming years. By 2018 however, the intervening years had provided a 3-year crash course in the Basic Fundamentals of Buharism and it was more than enough for me.

Something just had to give.

I had watched death after death after death. I had seen off friend after friend after friend. Kelechi went off to London. Desola went off to Toronto. Funmi went off to Montreal, then Chiboy went off to Toronto, then Chidiebere went off to Hamburg, then Harriet went off to Ottawa, then Mary went off to Texas, then Wura went off to Atlanta, then Timi went off to New Jersey, then Ella went off to Brisbane. And then my dad died.

The news had stopped being about anything I remotely wanted to hear about. Instead, I would regularly see headlines announcing that 500 people had been murdered by “unknown assailants” somewhere in Benue State. Actually the headlines wouldn’t even describe them as “500 people,"as in 500 electricians, farmers, housewives, children, plumbers, wheelbarrow pushers and shopkeepers. No, I would see something like “500 Dead In Fresh Agatu Attack.”

“500 Dead.”

It was as if 500 business cards accidentally fell into a puddle, or maybe 500 cupcakes got burnt in an oven. Five hundred human beings were murdered at leisure by heavily-armed, systematic, and organised non-state actors. It seemed like every other week, both in my personal life and in the country around me, there was a new event to suggest that I was witnessing the rapid, real-time implosion of the country I called home. The most intense feelings of bitterness and disappointment welled up as I slowly realised that the real-time degradation of my career aspirations, my family, my social life and my general lived experience in Nigeria was not a temporary blip, but a new long-term trend that had obliterated ‘Africa Rising.’

On the anniversary of my dad’s death in 2018, I visited his grave and spent hours thinking about what I wanted to do about this giant emotional weight I carried about with me. I thought about what he would do if he were in my shoes. He would probably offer a prayer for strength, and then deal with life like a Zen philosopher as he always did.

After all, that is exactly what he did during the 1980s when Nigeria last went through a similar period of total upheaval and mass emigration. As his friends and colleagues took their families and fled to London, Atlanta and Washington DC, David Snr. stayed in Lagos, prayed to his God, drank his black coffee, faced his government work squarely, and produced 3 additional children during what was at the time, the most tumultuous decade in Nigeria’s history. The man absolutely raw-dogged the 80s and came out on the other side with a wife, 4 children, 5 promotions, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure. He even had another child in ‘94 just for the craic.

An absolute legend.

But was his son like him?

He was not.

Dad was the type to accept what he could not change. I was the type to change what I could not accept. He was cool and passive. I was broody and intense. He believed that there was a ‘Jehovah’ somewhere maintaining a grand cosmic ledger of human fuckery in preparation for the day he would decide to do something about the world he apparently created. I had no use for gods and deities, and his ‘Jehovah’ meant as much to me as did Ọyá the Yoruba goddess of storms and lightning.

If there was one thing I had learned from my post-university years in the UK, it was that the world was a terrible place and you had to either accept being stepped on like bug, or fight for your place in it. Nobody was coming to help you, nobody was coming to rescue you, and nobody cared whether you achieved all your dreams or you fell in the shower, hit your head and died. You either took charge of your own destiny and survived, or you crawled into a sewer and waited for death - either way, the world was not losing anything of much value. Life was entirely what you made of it, and you were your only hope, saviour or messiah.

Lying there on my dad’s grave that day in June 2018 was when I made the decision that would define the next 5 years of my life. I decided that I would dedicate the ensuing few years of my life to aggressively attacking the things that I could not accept about the country around me. The system had become complacent and calcified in its malevolence to the extent that the basic human value of Nigerian life was being questioned. Pushback was desperately needed. The system needed an external correction.

The country’s public space needed an insurgent presence. A vigilante. A 1-man operation that would create the Nigerian equivalent of a Bat Signal. A well-connected member of the country’s elite who could also transform as needed into a complete and utter nutjob with a method to his madness. Nigeria was far too comfortable lying in its faeces with its eyes covered and nose plugged so that it could deny its own reality. Someone needed to rip off the nose plugs and take off the eye coverings so that Nigeria could once again know the most visceral discomfort and shame.

I decided that I would be that someone. Nobody asked me or thrust such an assignment on me. I simply decided that I had to choose whether to become a protagonist or accept the fate of an NPC standing in line to experience one of Nigeria’s endless catalogue of infuriatingly disrespectful and pointless deaths. I was going to make my stand and to that end, I would need a powerful weapon with which to wage my 1-man Jihad.

I already knew what my weapon would be.

2019 - 2024: The Gloves Come Off

It started with opinion columns and editorials in early 2019. TheScoop. CCN.com. BusinessDay. CNN Africa. The Africa Report. If anyone would give me a byline on their platform, I would sign whatever contract they put in front of me. Heck, even Opera News.

Then came Mercy Abang and the opportunity to start contributing investigative pieces to NewswireNGR in September 2019. During this time, I also found myself taking part in a research and documentation project for an NGO called PSJ Nigeria. That project ended up becoming the comprehensive report ‘Silent Slaughter: Genocide In Nigeria And Implications For The International Community.’ My most notable memory on this project was documenting a massacre in Kajuru, Southern Kaduna, and discovering - to my utmost disgust and very much against my will - what charred human flesh smells like.

Eventually, the report was completed and presented to US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Vice-President Mike Pence. As a direct result of this report, one of Pompeo’s last actions in office was to designate Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern for violation of religious freedom. It was not what we asked for, or anything close to it, but at least it was something. So naturally, as soon as Anthony Blinken took office as Joe Biden’s Secretary of State, one of his first major foreign policy decisions was to mysteriously take Nigeria off the list. To date, nobody can explain the rationale behind that decision.

At this point, I think I don’t need to go into a detailed description of how my subsequent investigative work became the journalistic equivalent of a blunt force instrument in the Nigerian public space, especially from 2021 onwards. This is because the very Substack you are reading is where most of this work was originally worked on and hosted. In the launch post, I was very unsubtle about what I want to do with this publication, which was then known as West Africa Weekly.

The gloves were off and nobody was off limits. Everybody could catch these journalistic hands, and everybody often did. The list of powerful people that I offended on these pages reads like a list of those who one should probably not offend in Nigeria. Allen Onyema. Isa Pantami. Muhammadu Buhari. Ahmed Idris Nasreddin. The entire Nigeria Immigration Service. Amnesty International Nigeria. The Nigeria Police Force. The DSS. Flutterwave. Loan sharks linked to the Chinese triads. BBC Africa. The serving president. A bank chairman. Multiple airlines and aerospace regulators.

At the peak of my troublemaking in August 2023, I was invited to speak on George Galloway’s Mother Of All Talk Shows about you know what. You know, that thing and that person. Yes. The most-read thing on this entire Substack publication. It was the only thing anyone wanted to talk about, and with good reason. I was newly settled in Nairobi at the time, fresh off the plane from West Africa after a security situation had forced me to leave, but I suppose I’m getting ahead of the story a bit.

The most important thing to point out about all of this full-contact investigative work is that while I had started off with the mistaken assumption that my work had no real implications outside West Africa and that its only limiting factor was my own sense of agency, I rapidly discovered that all those things I ever heard about neo-colonialism, meddling, interference and denial of sovereignty by a select group of countries and their diplomatic and intelligence systems, were completely true.

I realised this when I started to see a pattern in my work that went something like this:

Dig up promising lead about corruption or criminality by Nigerian government official or public figure

Follow lead down a rabbit hole that almost inevitably leads to Washington DC

Try to follow lead in DC using standard journalism tools like FOIA

Receive unfavourable response denying FOIA request because of “privacy exception” or “national security exception” because apparently, protecting Nigerian criminals was for some reason, very key to US “national security.”

This happened multiple times, with multiple story subjects listed above. Coupled with what had become a detailed understanding of Nigeria’s 2015 election as a US-backed regime change operation using a variant of the so-called “colour revolution” template, it was becoming clear to me that the masquerade I was fighting did not in fact, live in Abuja. Nigeria’s catastrophic national fall-off that began in 2015 didn’t just “happen.” Well paid White Men In Suits had sat in DC, discussed Nigeria in terms that even Nigerians did not discuss their country, and come up with a plan to make sure that the country of 200 million people would act in a way that was beneficial to “American interests.”

This plan apparently involved installing a hapless puppet who would distance Nigeria from Chinese economic and political partnership, and decimate the economy in the process. Nigerians being poor and miserable was good for the White Men In Suits. Nigerians being prosperous and having nice things was not good for the White Men In Suits. The disappearance of my helicopter pilot dream and the dreams of millions of Nigerians who died, emigrated, or found themselves living smaller lives since 2015 was merely the activation of a plan by those who had power for those who did not.

I had set off determined to be the biggest pain in Muhammadu Buhari’s scrotum that I could be. Now, along the way, I had discovered that Muhammadu Buhari was barely even the president, much less the actual power governing Nigeria. The Pan-Africanists and the YouTube conspiracy people whom I had once held in contempt were in fact, correct about how the world really worked.

During all of this, I was funding my work by myself for the most part. I mean, I did often ask readers to consider supporting my work with a paid subscription, and I would strategically dot my Substack stories with a button like this:

But did the millions of Nigerians at home and abroad who read the stories here, plus the 57,000+ free subscribers think it was worth it? I think we all know the answer to that question already. Our people will always be our people. We are who we are.

Nonetheless, I had to do what I had to do. Since I was doing it primarily for myself, having embarked on this 1-man war that day at my dad’s grave back in 2018, I had to keep going until I felt like I had hit my limit. I didn’t know what my limit was or what hitting it would feel like, but I knew that I would know when the time came. It came earlier than I thought.

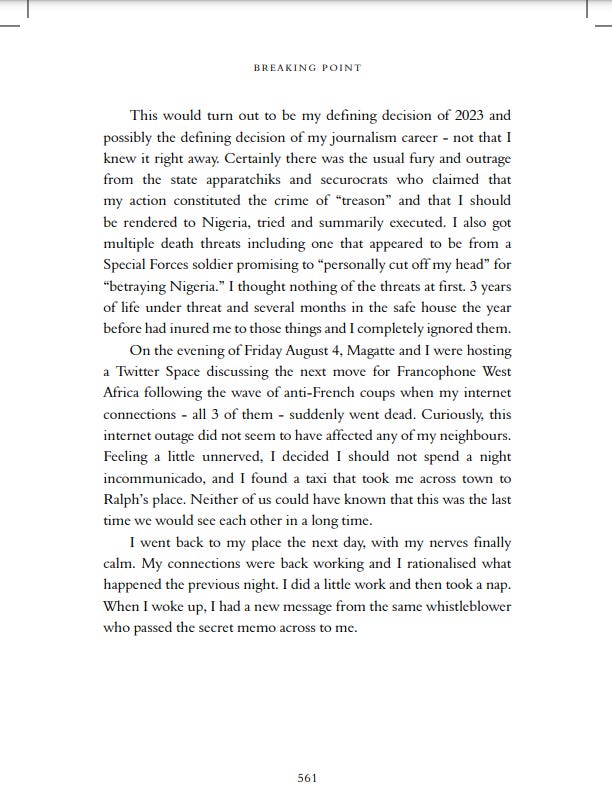

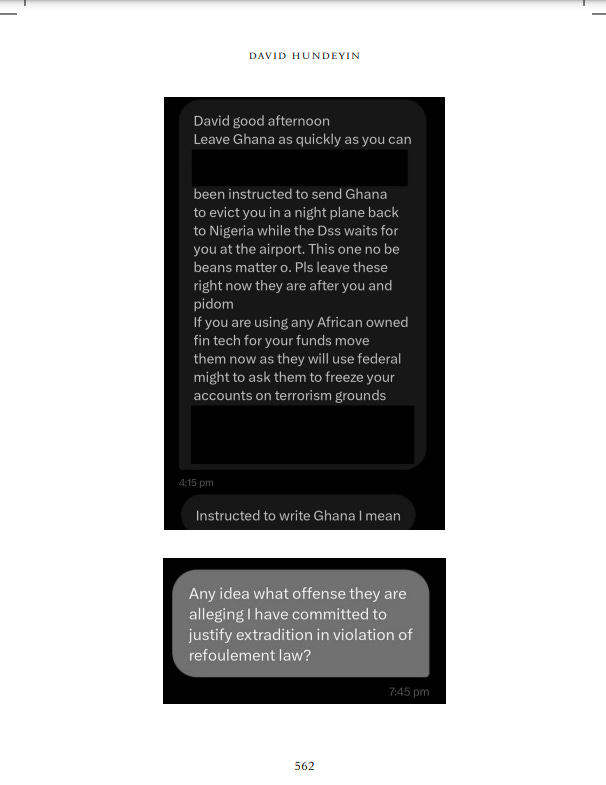

To be precise, it came on August 5, 2023. It all started when I received a leaked document on August 2. This document, which appeared to originate from the Defense Headquarters, contained attack instructions for the Nigerian military to illegally invade Niger - an invasion that offered zero geopolitical benefit to Nigeria, and was clearly being pushed on behalf of the same oyibo masquerades that have been popping up multiple times in this story. I decided to publish the document to my nearly 1 million-strong Twitter audience at the time.

I have told the story of what happened next multiple times, but I will do so once again using excerpts from the final chapter of my book Breaking Point, a Twitter thread I posted about this incident, and some never-before-seen visuals to give the reader an idea of how my life got turned upside down because of a choice I made. Here goes:

Anthony Blinken is a Wanker

By now, the reader should have noticed a pattern here about my effort to fight an impossible 1-man war on the Nigerian status quo, and who seemed to keep showing up as the eternal opp on the other side of the fight.

From ruining Nigeria’s ‘Africa Rising’ moment in 2015 with the regime change operation that took out a president growing the economy at 7 percent annually and replaced him with some guy who met Angela Merkel and described her country as “West Germany,” to enabling the worst of the Buhari government up to and including the Lekki Massacre, to going after me by weaponising a VOA “fact check”, to rinsing the Red Scare tactic in a smear attempt aimed at a platform I work with, down to the algorithmic suppression of my Twitter account whenever I tweeted the keyword “State Department,” the US government has spent the past decade systematically trying to ruin my life and those of the 210 million people who live in Nigeria.

It is no exaggeration to say that the US State Department is in fact, the biggest mortal threat to the existence of 210 million Nigerians alive today. Its unprecedented meddling, fiddling and interference in Nigeria’s internal affairs for the purpose of keeping the country locked in an economic and political role that unelected White Men In Suits from Washington DC assigned to it, is what directly led to the multiple economic and security catastrophes witnessed since 2015.

These pages upon pages of death certificates in the Silent Slaughter report? Those are the results of American geopolitical actions in Nigeria and the Sahel. The US-led destruction of Libya and empowerment of Muhammadu Buhari are actions whose costs can be directly measured in Nigerian deaths.

The utter immiseration of the Nigerian people in 9 years, shrinking from No. 1 and fastest growing in Africa to No. 4 in Africa - and shrinking - has a death toll attached to it too - potentially even greater than the measurable genocide toll. Exactly how many Nigerians died because 50 percent of their economy was obliterated in just 9 years, we will probably never know. And that’s not to mention the hidden costs, such as the loss of future productivity due to the unprecedented emigration over the past decade.

How many families have been permanently fractured because siblings, spouses, parents, children and cousins had to find their respective ways to mainland Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US? Do such records even exist?

Realising the true size of the problem facing everyone and the identity and nature of the big masquerade behind the protracted destruction of Africa’s erstwhile lodestar country, plus the unwinnable nature of my Pan-Nigerianist 1-man Jihad, family members and friends have regularly asked me, “Why bother, David? Why not just let it go?”

Over the past 18 months, I have increasingly found myself asking the same question. After all, as far as my initial goal of re-acquainting the Nigerian public consciousness with shame and discomfort goes, it is visible to the blind and audible to the deaf that I have not succeeded. The sheer inertia of the Nigerian mind fed by decades of pernicious social engineering has made it such that even many reading this will be fundamentally unable to comprehend the value of what they are reading beyond it being a cool story.

So knowing how unwinnable this 1-man war is, why do I bother then? What is the purpose of this apparently doomed show of defiance? I’ll try to answer that question with a story:

Back in 1991, shortly after the breakup of the Soviet Union, at a time when war between NATO and North Korea was starting to look like a thing that could happen, North Korean supreme leader Kim Il-Sung called his top generals together for a meeting to discuss strategy for a war against the USA.

After hours discussing the nuts and bolts of prosecuting this war, Kim asked everyone in the room a question that they did not know how to answer. He asked,

"What if we lose? What will we do if we lose?"

The generals didn't want to answer this question because to even acknowledge the possibility of losing might be interpreted as disloyalty or even treason. At the same time, "We cannot possibly lose" was not a useful answer, and Kim certainly wasn't looking for delusional optimism in his military commanders.

Kim's son, Kim Jong-Il, who was present at the meeting, was the only person who spoke up. His answer was simple:

That answer is one of the most inspiring things I have ever read in my entire life.

I can hear your dispproval - why would David express admiration for a dictatorial hermit regime’s plan to carry out the most expensive tantrum in history if a hypothetical war did not go its way? The simple reason is that I have always found something deeply compelling and somewhat admirable about the notion of North Korea seeing itself as the centre of the world.

If the inhabitants of that patch of cold, rocky land - poor in natural resources and seemingly condemned by geography to eternal poverty and irrelevance - can see themselves not only as a key part of the world, but as centrally important to it, then why should I, a native of the planet's most fought-over continent, not see myself as a main character in the world?

Between themselves, the dynastic trio of Kim Il-Sung, Kim Jong-Il, and Kim Jong-Un turned a barely-hospitable corner of East Asia into an impregnable, nuclear-armed fortress that absolutely nobody dares to take levities with. Unlike Africa, they have no especially huge amounts of gold, bauxite, oil, coltan, diamonds, copper, arable land, or sunlight. In fact most years, they can barely grow enough grain to keep their population fed.

And yet, in a world where independence and sovereignty are only truly guaranteed by nuclear bombs and ballistic missiles, they have managed to build those things out of Kimchi, rough potatoes, some Chinese aid and a whole lot of sheer willpower. Mind you, nobody particularly wants North Korean territory - its most valuable geographical asset is actually its 1,420KM border with China - yet it sees itself as not just a key player on the global stage, but the world's main character.

Meanwhile in Africa, the continent that supplies everything to the world and also controls the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal - the 2 most important shipping lanes in global trade - nobody really seems to understand or believe that they are part of the world, let alone among its main characters. Nigerians especially, are afflicted with a psychological paralysis that seems to prevent us from understanding that we have the right as freeborn citizens of a sovereign country, to fight for our place in the world

That is where I fundamentally differ from that interesting entity known as “the typical Nigerian.” I have seen not only the size of the world, but also the promise and potential of my people. The things that were happening in 2015 were not hallucinations. They were real. All it took was about 10 years of stable, half-decent leadership, and Nigerians were building cars and on the verge of assembling jet fighters. If the malevolent foreign influence can be isolated and removed, I know my people have limitless upside.

In any case, over and above simply needing to extricate the destiny of my civilisation from the grasp of diseased intelligence extensions of diseased countries led by diseased folks like Anthony Blinken, I cannot stop thinking about Korede. I haven’t been back to 58, Jagunmolu Street since I moved out in 2018. Life is a lot different now, and a lot of things did not survive my personal transition that began in 2018, including even the marriage I was in at the time.

Yet 6 years later, I can sometimes still hear Mummy Korede wailing “KOREDE OOOO!” in my quiet moments in the small hours of the morning. I can still see the charred, dismembered corpse of a child in Kajuru. The phantom smell of burnt human beings still clings to the interior of my nostrils 5 years later. If you want to know what it smells like, think of the early stages of roasting a goat, only 50 times worse because you know it’s not a goat.

I remember all my memories and I feel all my feelings. I cannot unsee what I have seen. I cannot forget what I have come to know. Consequently, my only existential purpose continues to be to do whatever is in my power to reassert the inherent value of West African life. Anthony Blinken and his fellow geopolitical svengalis may see African lives as abstract, unimportant rounding errors in the complex calculations of global geopolitics, but - this part is important - I don’t have to agree.

There are several ‘friends’ I once had from the US-funded global civil society and media spaces who actively avoid me nowadays because I have chosen to push back instead of being a nice colonial child of Empire who watches politely as the Empire destroys his home. This to them, constitutes a tremendous act of societal heresy. I wish genital warts on all of them, because I know some of them are reading this. Nobody owns or controls me, so I am free to say that.

I am also free to state on record that if the world had any justice, Anthony Blinken, Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton and Kamala Harris would die in prison and never see the light of day again. Yes, I know that will probably never happen because the world has no justice, but I can at least say that I hope it does, because I understand that my interests and theirs are diametrically opposed to each other.

Let me reiterate in less eloquent language - I do not give a single fuck about the United States of America or its “national interests.” I come from a country that is being thoroughly destroyed by the United States because of these “national interests” that include protecting criminals and lying in court. In a way, the most liberating thing about the past 6 years has been the realisation that nothing is actually fundamentally wrong with Nigeria after all - it’s just being parasitically puppeted by an even sicker country.

Interestingly, the parasite has entered a death spiral of its own. Whether Nigeria will be able to exorcise itself of the diseased American parasite before both countries die together remains to be seen. If the host manages to free itself and leave the parasite to die the way the USSR died, happy days for all. If Nigeria insists on dying alongside its American bodysnatcher however, then I will at least have one of the best seats in the house.

And if there is an afterlife, all I would like is to go one-on-one with Anthony Blinken.

Thank you, David. You may not hear it or feel it often, but that you for giving a fuck about Nigeria. You've opened my eyes and that of my husband and I'm sure many others to what lies underneath the surface and I'll be forever grateful. I never look at anything, especially Western issues as surface. I always ask, "What do they stand to gain?" Or "what are they trying to do with this?"

Thank you, David.

Your labour over Nigeria will never be in vain.

While it is easy to place all the blame on Nigerian leaders, we must also acknowledge the significant political and economic influence wielded by the United States and Western powers. These nations often take strategic actions to safeguard their interests globally, exerting pressure through various means such as economic sanctions, political interference, and military interventions. Historical examples like Iraq, Haiti, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo illustrate how external forces can shape the destiny of nations.

In Iraq, the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, justified by claims of weapons of mass destruction, destabilized the country and left long-term consequences for its political and economic structures. Similarly, Haiti has experienced repeated foreign interventions, including U.S. military occupations and economic policies that have contributed to its ongoing instability. In the Congo, Western interests, particularly during the colonial period and the Cold War, fueled conflicts over natural resources, leaving a legacy of exploitation and unrest.

While the shortcomings of Nigerian leaders cannot be ignored—especially their roles in corruption, poor governance, and mismanagement—it is essential to understand the challenges they face, both internally and externally. The interplay between local governance and international pressure creates a complex environment that often hampers progress.

We share a common adversary: systems of oppression and exploitation that transcend borders. Some individuals have resigned themselves to these forces, becoming complicit or defeated, while others, like you, continue to resist and advocate for change. This struggle is not easy; confronting powerful systems of control requires immense courage and resilience.

One person standing against an oppressive system may seem like an insurmountable challenge, but history shows that even a small act of defiance can spark a broader movement. This spark can ignite a revolution that has the potential to transform the entire nation—perhaps within our lifetime.

Finally, I want to encourage you to continue your efforts. Your dedication contributes to a growing wave of resistance and hope for a better future. Keep up the good work.