#EndSARS

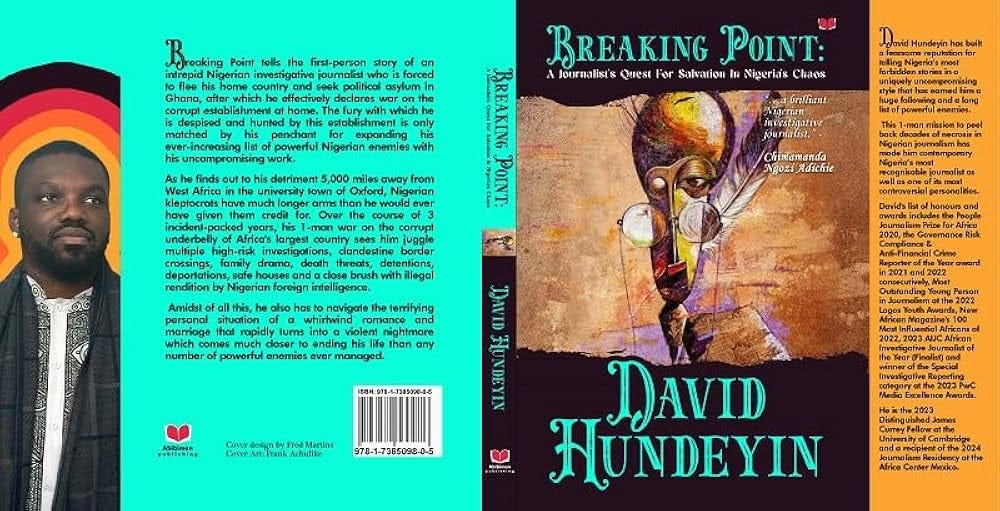

Chapter 1 of my sophomore book 'Breaking Point: A Journalist's Quest For Salvation In Nigeria's Chaos'

I am not a superstitious person. Far from it.

In fact, I started self-identifying as atheist at the ripe old age of 17, despite living in a country that is as friendly to atheism as outer space is to swimming. I’ve never been big on any of the spiritual/religious stuff, but I do have something. Call it a spidey sense. Premonitions. A weird ability to sense major incidents or changes in my life just before they happen. This has been happening since I was a teenager in Okada town during a short-lived stint at Igbinedion University in 2008.

There, apparently forgotten by the world while dealing with the unholy triple combo of malaria, dysentery and typhoid during an episode that came close to truncating my 18-year-old life, I had a lucid fever dream. In the dream, I had a successful conversation with my parents about leaving the concentration camp university in Darkest Edo State and moving to England to study Creative Writing. Exactly 4 weeks after this dream, I found myself in Lagos having that exact conversation with my parents, and in September 2008, I boarded a KLM flight to Amsterdam enroute Hull, where I would eventually finish with a degree in Creative Writing in 2011.

3 years later, during my NYSC year in Ekiti State, I had a strong premonition that something terrible was going to happen one night in my little studio apartment in Ifaki. I decided to step out for no reason in particular and pass the night at a friend’s place in Ado-Ekiti. The next day when I returned, I learned that armed robbers had attacked the area and kidnapped a next-door neighbour who worked at the Federal University in Oye. She died in their custody.

On the night of June 2, 2017, I had a similar amped-up, spine-tingling sensation while lying on my sofa at 58, Jagunmolu Street, Bariga. I found out the reason the next morning, when I got a call from my mother whom I rarely ever spoke to, so I knew it must be important. It turned out my dad just had a stroke, and so I would spend the next few hours watching him die a completely unexpected death in slow, excruciating increments while we waited for an ambulance that simply didn’t show up, for some reason. When it did show up, the driver casually informed me, “We don’t carry dead bodies,” after which said ambulance duly turned around and zoomed away, leaving my dead father lying at my feet.

I got that feeling again in September 2018, when after 3 barely tolerable years of marriage, I suddenly had a strong feeling that the end of that 5 -year relationship was coming before the end of that month. I didn’t know when exactly it would happen or how - for that matter, we were not even on particularly bad terms at the time. Somehow, I just knew. I couldn’t tell you how if I tried. Sure enough, on September 28, 2018, there she was packing her bags to leave, and there I was watching it happen with a sort of mild fascination, like I was having an out-of-body experience.

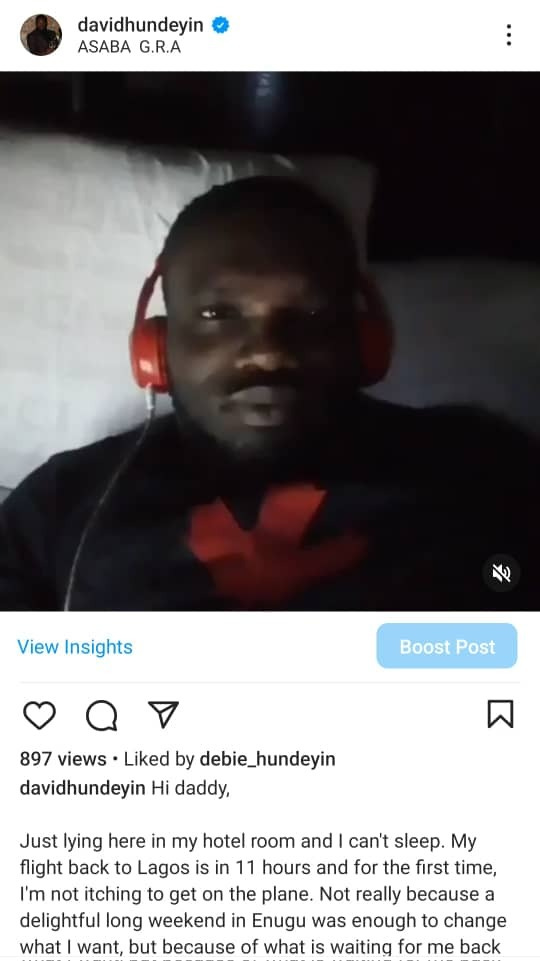

This thing happened again in August 2020, when I found myself passing the night in a cheap hotel room in Asaba ahead of my return flight to Lagos the next morning. I had just spent a weekend at Nike Lake Resort with my girlfriend who was doing her NYSC in Abakaliki, and I should have been pretty much satisfied with life at that point. I had recently landed a new $2,000/month news reporting gig at BeInCrypto.com, and my boss at BusinessDay, Frank Aigbogun had just called to let me know that my weekly column had become the most read thing on his entire newspaper.

Consequently, my BusinessDay contract was tripled and so I found myself in the relatively comfortable situation of earning between N1.3m and N1.8m monthly as a 30-year-old bachelor in Lagos. I had just moved into a new serviced apartment at TPDC Estate, Lekki and I really should have been having the time of my life. But there I was on the imitation Mouka Foam mattress in Asaba GRA, tossing and turning on the night of August 25, because I could not shake the sensation that something which would change my life significantly over the ensuing few weeks was in the offing. I was stressing out so much that I actually did a cringey Instagram post about it.

Somehow, I knew with every fibre in my body that something was coming, but not even that spidey sense could have prepared me for just how big it was when it came. If you were to go back in time to August 25, 2020, and tell the version of me that existed back then that in 2 months’ time, I would abandon the comfortable life I had built in Nigeria and seek asylum in another country, I would have burst into laughter. If you were to further tell that version of me that fast-forward a couple of years, and I would be speaking remotely to the 54th Session of the UN Human Rights Council from a hideout in Nairobi while on the hit list of a powerful West African organised crime syndicate, I would have thought you truly insane.

All I wanted to do was get back to Lagos, draft my 3 daily 450-word stories for B.I.C., work on my 5 monthly investigative pieces at NewswireNGR, submit my (now thrice weekly) BusinessDay column on time to Caleb Ojewale, my editor who always had to deal with my hit-and-miss record with deadlines, and spend my spare time living my fabulous single life. While my girlfriend was away in Abakaliki, I had a few “sneaky links” who made life in Lagos very bearable. When I wasn’t in the mood for physical extracurricular activities, I had OJ to go out and explore Lagos with.

OJ and I went way back - all the way to 2008 in Hull. We had very different personalities, but remarkably similar backgrounds, education, worldview, plus a constant tendency to project an air of ironclad arrogance to those who didn’t know us, while secretly being sweet and vulnerable people behind the mask. OJ was the closest thing I had to a best friend in Lagos, and we would meet at a different restaurant every weekend to trade war stories and share our endless collection of inside jokes at the expense of the mass of humanity around us. He also functioned as a sort of de facto sounding board for my stories and columns. If you wanted to know what would be in the headlines and Twitter trends next week courtesy of my upcoming NewswireNGR investigation or BusinessDay column, you could probably find out from OJ, if he would tell you.

When I first mentioned the Police Reform Act 2020 and my plan to write a comprehensive review about it to him, he certainly was not especially enthused. He sounded bored even. A journalistic review of police legislation? “That’s so boring,” he said, in the voice that was the sonic equivalent of a housecat’s unimpressed facial expression. I almost didn’t end up doing it. Generally speaking, I tended to model a significant amount of my work around his criticism, even though I would never admit that to him. You really couldn’t go wrong with a friend who channeled “art critic who writes for Le Monde” in a slightly disappointed Garfield voice.

For whatever reason, I still ended up doing the story. As usual, it went 17 different types of viral. As usual, opinions were split on it. Some chose to see the points that were made in the analysis, while others chose to take a personal issue with whatever it was they had decided to have a problem with when they woke up that morning. It wasn’t anything that hadn’t happened 1,000 times before. I had long since gotten used to the reality that my efforts to present large chunks of complex information in addressable pieces to my Nigerian audience, was equally matched by the efforts of a large part of said audience to deliberately mishear, misread, misunderstand and misrepresent whatever was presented. I was basically carrying out long-read investigative journalism for the South Park rabble.

This time however, was a bit different. The hubbub did not die down after 72 hours like it normally did. From the moment I published that article on September 25, 2020, up until I realised why my spidey sense was jangling the following month, screenshots and excerpts from this story kept doing the rounds on Twitter and WhatsApp. I started to think, “Maybe I have actually done a thing here.” I thought maybe the enhanced public outcry would get the (already signed) bill sent back to the House, since it had not yet been gazetted. I could not have predicted in 1,000 years that the ensuing 3 1⁄2 weeks would turn into some of the longest weeks of my life up until then.

And then that video emerged.

October 1-19, 2020

You know what video I’m referring to. The one with the police officers stopping a young man driving a Lexus, throwing him out with the car still in motion, and driving off leaving him for dead. Some claimed that the man died, and others claimed that he was merely injured. Some even claimed that the event did not happen at the time the video started making the rounds on social media. In fact, the only universally verifiable thing that seemed to be known about the video was that it was filmed in Delta State.

All of which was completely immaterial.

Viral article, meet viral video. Flame, meet petrol.

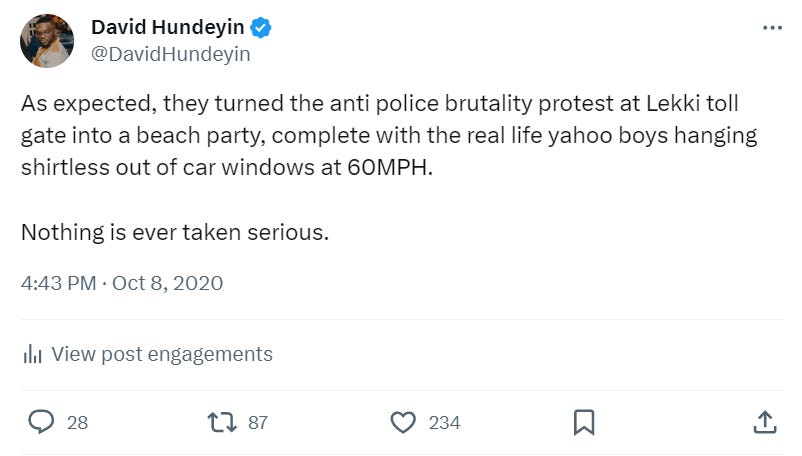

You know that video of the guy who is trying to heat up the charcoal in the grill in his garden, and then he opens a can of petrol over the open flame and pandemonium ensues? That was pretty much how the events of the first 9 days of October 2020 played out in front of my eyes. Not least because when the #EndSARS protests migrated from the internet to the street for the first time, I initially found them completely absurd and impossible to take seriously. On Thursday October 8, 2020, I had just finished filming a few episodes of Patito’s Gang at Balarabe Musa Crescent, VI, with Prof Pat, Ifechi, Cheta and Eugene. I was in my Uber texting a sneaky link on my way back to Chevron when I saw what looked like a carnival at the Lekki Toll Plaza.

I didn’t see a protest. I saw a joke. Shirtless boys puffing weed and hanging outside the windows of black 2012 Toyota Camrys while the onlooking girls whooped and whistled. This? This was what the people on Twitter were on about? This was the #BlockLekkiTollGate thing I had seen trending that morning? Clearly, these were a bunch of jokers who were here to catch their jollies, and I put out a suitably unimpressed tweet.

To my mind, Nigerians were people without any sort of ingrained protest culture, so whatever they called a protest would be useless, just like what I saw on October 8. I didn’t leave the house on October 9, but I followed the conversation on Twitter and over the course of that day, I began to realise that I had committed the cardinal error of drawing a conclusion about something I had not really bothered to examine. I had my first ‘Come to Jesus’ moment when I found myself scrolling through my Twitter timeline for 20 solid minutes and every single tweet had the #EndSARS hashtag. Nobody was talking about anything else.

The next “uh-oh” moment came the very next day, when different groups of protesters staged simultaneous marches around the country. While the one close to me in Ikoyi was a largely sedentary affair led by a small group of podcast belles, it was the one in Abuja that caught my eye - not only because of how violent the police response was, but because of how defiant everyone in Abuja seemed to be. Something I can admit now is that up until that point, I had always been quietly frustrated at how despite pouring my heart and soul into my work, it only seemed to end up being consumed and ultimately wasted by the South Park rabble. For the first time, I saw something else. I saw an opportunity for action. I saw resolve. I saw defiance. I saw anger.

I saw adventure.

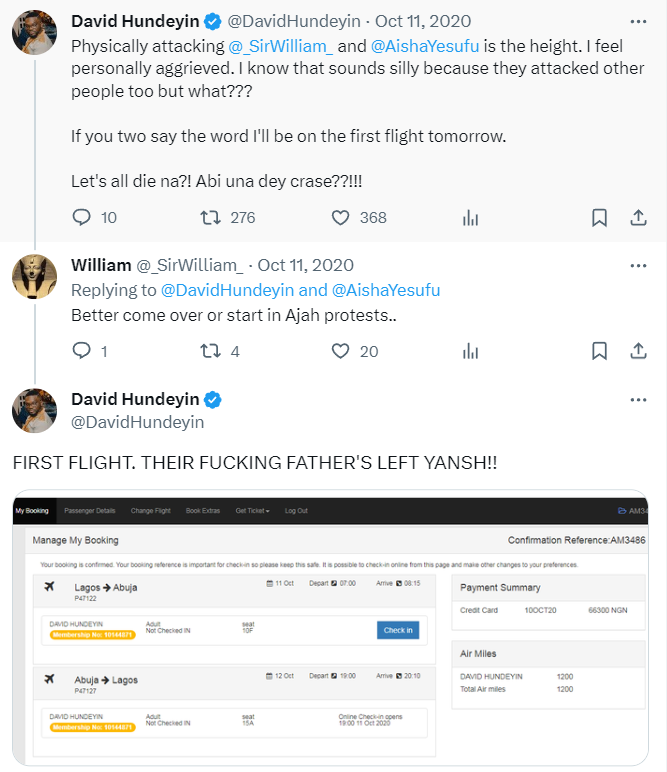

I reacted to it the way a thrill seeker reacts to his first hit of pure cocaine. William, Ndi and Raphael couldn’t be on the streets of the capital fighting for my freedom while I sat in Lekki booking Airbnbs for the next time I wanted to cheat on my girlfriend. This was the revolution and I couldn’t not be part of it any more than I couldn’t not be the artsy, headstrong black sheep of the Hundeyin family. Rebellion had been my single recurring personality motif since I was old enough to talk. I had always been one walking, talking bag of dynamite just waiting for the right fuse to be lit.

And this was it.

In hindsight, announcing the date and time of the flight I booked to join the Abuja protests the very next day was not the smartest move in the book. I might as well have worn a “Please Arrest Me When I Land Because I’m Here To Cause Trouble” placard around my neck. But you know, ‘Vive La Revolucion’ and all that. Finally Nigeria’s youth were standing up to be counted, and goddammit I would be there no matter what. If there would be teargas, I would be gassed with my brethren and sistren. If the police would attack, my backside was not worth more than those of Ralph and Ndi who had borne the brunt of the brutality the day before. One for all and all for one.

Linked arm-in-arm like a 1960s Civil Rights rally in Alabama, we marched from Unity Fountain toward the Police Force HQ at Louis Edet House. Now we all thought of ourselves as pretty brave for doing that, but if awards were given out for bravery on that day, they should all have gone to one person - Raphael Adebayo. Ralph was not just a key protest organiser, but also the person responsible for leaking the personal phone numbers of Femi Adesina and Sadiya Umar Farouq to the public, with predictable results.

Leading from the front with the natural train horn he had for a voice, he led the chorus:

“HOW MANY PEOPLE SOJA GO KILL O,

HOW MANY PEOPLE SOJA GO KILL,

EEEEEEEEH THEM GO KILL US TIRE!

EEEEEEEEH THEM GO KILL US TIRE!

EEEEEEEEH THEM GO KILL US TIRE!

HOW MANY PEOPLE SOJA GO KILL!”

As we neared Louis Edet House, it occurred to me that my cousin Benjamin - then a police officer working with the IGP - would himself be inside the Force HQ which we were attempting to picket. I whipped out my phone and sent a grinning selfie to his WhatsApp number. As usual, he didn’t respond. This was part of our regular Tom-and-Jerry routine. He was part of the establishment and I was the loose cannon trying to burn down the establishment. We both knew our roles and respected each other. If I ever needed to torpedo his career with my pen, I would do so. If he ever needed to shoot me in the face to maintain law and order, he would do so. We both understood the role each other played, and we were both extremely loyal to our chosen careers. In another lifetime, we would have been best friends. In this one, sentiment had to take the back seat. We both had to do what we had to do and we respected each other for it. I actually liked Benjamin a lot, but he was on their side - and vice-versa.

We didn’t have to wait long for the police response. Out came the water cannons. Then came the teargas. I’d been marching arm-in-arm with William and Kevwe, but suddenly we all lost each other as we scampered. Police officers on foot wielding plastic pipes came after us in hot pursuit and I discovered how quickly I could improvise in emergency situations. While everyone else ran straight back up the road, I detoured right and took cover under a kiosk in front of Eagle Square, flattening myself to the ground under the kiosk. But not before tweeting a quick video update. Again, not the smartest move to visually document my location in real time, but in those heady old days of 2020, what did we know?

Not much. We did not know much.

Having fought the power to my heart’s content, I boarded my return flight to Lagos the following evening, convinced that we had scored a victory. We had after all, got the president to issue a statement dissolving the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), so despite the obvious insincerity from the government, we had in theory ended SARS. Even as it quickly became clear that fighting the power in Abuja on October 10 and 11 had not in fact brought the protest to an end, I remained in my fool’s paradise at TPDC estate.

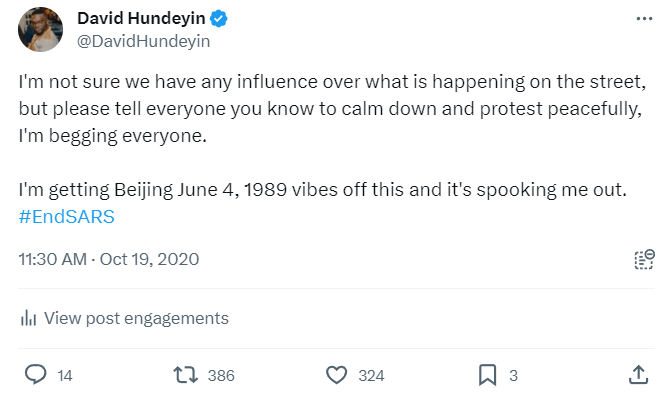

October 20, 2020

On the morning of October 20, I had to go out to fill my gas cylinder and I had a long telephone conversation with Yemisi. She was almost in tears, begging me to please tell people to leave that damn toll gate. Everyone knew that something nasty was going to happen that night. I knew it. She knew it. The people who showed up to remove the CCTV cameras knew it. It wasn’t a secret. In fact I had gotten such strong heebie-jeebies about it that I actually put out a tweet the day before, explicitly stating what I could feel was about to happen. Again, I couldn’t possibly tell you how I knew. I just did.

I had a neighbour at TPDC who was a chef. He and I had a long conversation that afternoon where he said that he was going to the toll gate to join the protesters and the military would never dare to shoot because they would all be holding and waving Nigerian flags and singing the national anthem. I have no idea if he actually went, but I do know that I never saw him again. My next memory from that day was taking a nap around 6PM and being woken up by a sort of communal scream around 6.50PM. It was like the walls and foundation of the building itself were yelling, such was the force with which everyone in the building was shouting.

The internet was very slow all of a sudden, but someone on my floor was able to stream what I would later learn was DJ Switch’s Instagram Live video, and he had hooked it up to his bluetooth speaker for everyone to listen in. Still the full import of what was happening did not sink in until I checked my WhatsApp and I saw William’s update:

“THEY ARE SHOOTING PEOPLE AT LEKKI TOLL GATE!”

I became numb and disoriented for a few seconds, then the mental equivalent of muscle memory kicked in. I called my girlfriend. She did not answer her phone. The momentary rush of annoyance this elicited gave me a jolt of adrenaline and brought me back to myself as I tried to reach her. Eventually she answered, all smiley and oblivious as always. I ended up laying into her for a good minute for not monitoring her phone or staying up to date with the news cycle. To be fair, she kind of deserved it.

My phone rang. It was OJ. I answered, expecting to hear a frenzied version of his regular stammer on the other end. I heard nothing. Then I heard a choking noise I had never heard before.

OJ was crying.

Weeping, actually.

There have not been many moments in life where I have been truly lost for words and unable to find anything to say. This was one of those few moments. I just stayed on the phone and listened to him weep his heart out. Eventually, after contacting family to confirm everyone was OK, it was time for me to take stock of the situation. These guys had just done a Tiananmen Square in the closest thing that Nigeria’s largest city had to a Tiananmen Square type of location. This meant that all bets were off. If they were willing to do this, then everyone else considered to be a problem to them would be next.

NEPA or PHCN or Eko DISCO, whatever the fuck it was called, chose that exact moment to get funny with the electricity phases. My apartment was thrown into darkness while the corridor outside had power. I examined my situation logically. I had just made some major lifestyle purchases for my apartment and I had also just rented and furnished a flat for my girlfriend in Abakaliki because no love interest of David would live in a corpers’ lodge. I had maybe $1,200 left with me in total and no valid visas, since I had not planned to travel for at least another 6 months. If I had to leave the country at short notice, I would need nothing less than $3,000 to get to somewhere I could lay low and think for a while.

Right then, with my neighbour’s bluetooth speaker still blaring the livestream of the ongoing massacre in the background, I took my laptop and MiFi router out to the corridor and logged into my B.I.C. wordpress backend. It was time to take on some extra work and make some extra money. I needed to leave the country pronto, and only a good last 10 days of the month could bump my paycheck back up to $2,000 because I had been slacking off for a few days. As the sound of machine gunfire from the live stream continued playing in the background, I sat on the floor in the corridor and got to work drafting “Kik Concedes to $5 Million SEC Penalty.”

The next morning, Dipo called. “So bro, when are you leaving?” was the first thing he said. Neither of us needed to ask a question or offer an explanation. We both saw the same picture. “Soon,” I told him. Next came a message from a friend at the PR agency where I used to work. MTN was suffering a PR nightmare due to their rumoured involvement in slowing down internet speeds during the massacre, and the agency had been briefed to fix it. I was being reached out to as a friend of the house and a connected journalist to help clear MTN’s name by putting the word out that they had nothing to do with the massacre or the internet slowdown. Among the trove of documents sent across to prove their innocence was a statement from ALTON, the umbrella body for Nigerian telecom operators.

It read as follows:

“All members of the Association of Licensed Telecom Operators of Nigeria (ALTON) receive with deep sadness, news of the killing of unarmed protesters in Lekki, Lagos last night. We believe there was nothing warranting the killings. 20-10-2020 will forever be remembered in our history. We sympathise with the families of those who were cut down in their prime and pray that God will give them the fortitude and strength to bear the irreparable losses. The downtime has been compounded by fibre cuts that have occurred across major routes in the metropolis resulting in congestion and poor services. Unfortunately, movement restriction and the volatility of the streets have conspired to ensure the outage persists because engineers have not been able to access the sites to fix the problems. At the moment, the affected member operators are exploiting all avenues to remedy the situation. Engineers are working round the clock to access the sites, while in the interim there are plans to optimise coverage from other hub sites, deploy mobile sites and reroute traffic on fibre links as a stop-gap solution to the most impacted locations.”

The reason behind the service outages during the massacre was strategically buried in the middle of this passively-worded statement – “fibre cuts that have occurred across major routes in the metropolis.” In plain English, this means that someone cut the fibre optic cables that supply Nigeria with high speed internet in several locations across Lagos simultaneously, causing network interruption – or sabotage, as you might otherwise call it. I read the statement several times and shared it with Dipo and Gbemiro to confirm that I was indeed reading what I thought I was reading. They confirmed that I was.

Essentially, this statement implicated whoever knew where the cables were buried and had the technical capacity to disrupt them in multiple locations at once. Since the networks had distanced themselves and made their disapproval clear with an unusually strong statement, that would leave only one other suspect with the same information and physical tools that the networks had - the state and/or federal government.

Nigeria’s fibre optic cable infrastructure originates in Lagos where it feeds from an undersea cable. From there, it fans out across the country to service Nigeria’s estimated 112 million internet lines via a vast network of mobile base stations owned and maintained by IHS Towers. Fibre optic cables are typically laid underground and specifically in such a way as to minimise the potential for network disruption due to external disturbance.

In February 2020, Airtel Nigeria reported that it suffered 1,022 fibre cuts in six months. 405 of these cuts were attributed to roadworks, and 617 were attributed to vandalism. If we extrapolate from this that roadworks and vandalism are to blame for most fibre cuts in Nigeria, it then begs the question – What roads were being worked on, or what vandals were digging for cables to steal at 6.50 PM on Tuesday October 20, hours after a 24-hour curfew had been declared by the Lagos State government?

For the “series of fibre cuts” to have taken place and to do so in such a manner as to disrupt network services almost simultaneously, indicated a coordinated attack on network infrastructure that night. In other words, some entity working outside of the knowledge of the mobile telecom providers intentionally and systematically interrupted the fibre optic cable providing most of Nigeria with its high speed internet access in a manner timed specifically to coincide with the Lekki Massacre.

November & December 2020

I had to break this story of course, but I also knew that doing so before I left Nigeria would be as good as signing my own arrest warrant. Barely a year after Uncle Biodun - more on him later - had threatened me with detention in a DSS 7th sub-basement cell, I knew that there was no need to tempt fate. I started to plan the specifics and particulars of my exit. I told almost no one about my plan, because I did not know who to trust at this point. Only OJ knew that I was planning to leave. Not even my family got wind of it. None of this, by the way, was an overreaction. I had heard from insiders that the NIA had compiled a no-fly list made up of people considered to be protest ringleaders and troublemakers. With my posting-plane-ticket-on-Twitter antics in addition to the reputation I had already built up with my work, it would be a miracle for my name not to be on it.

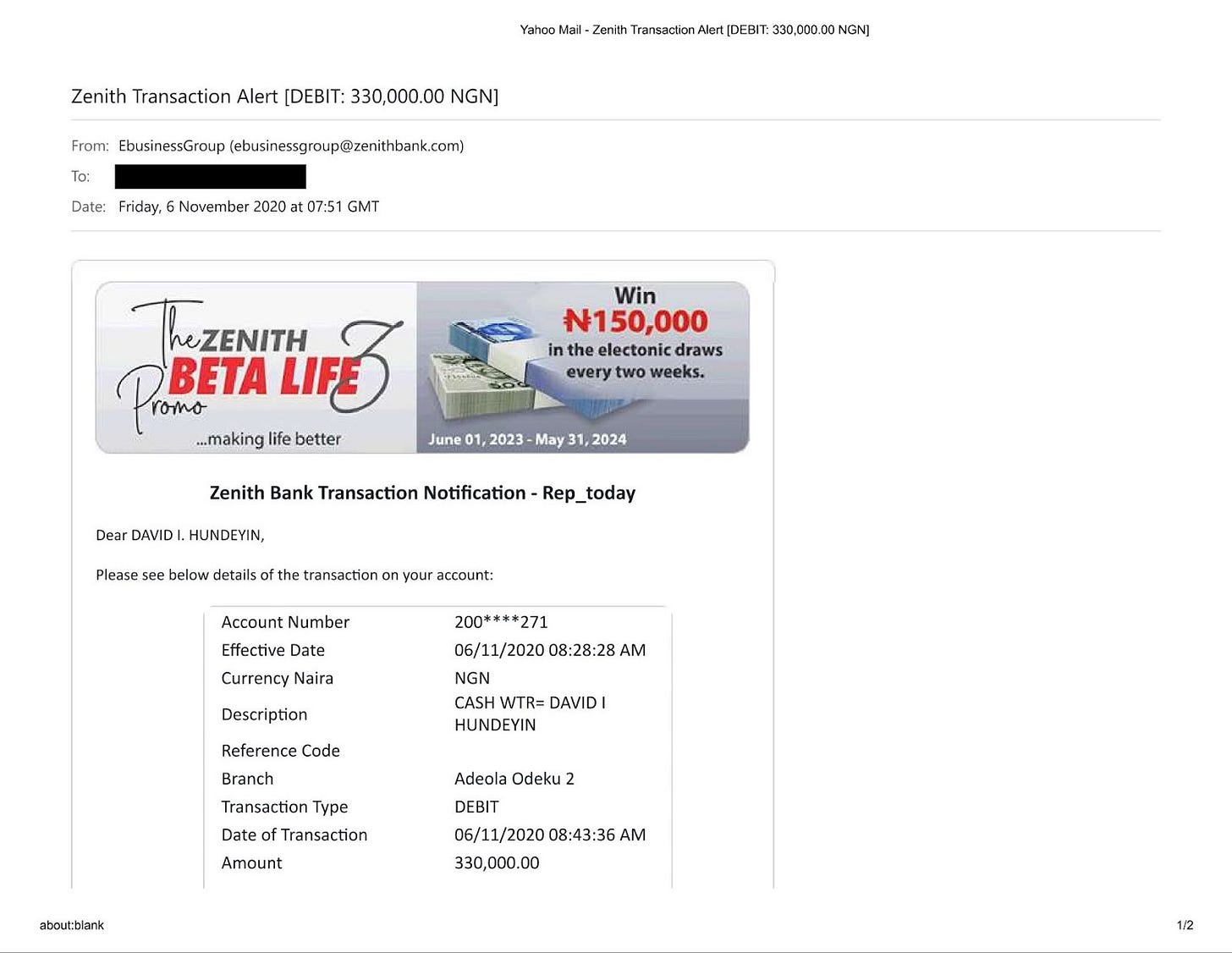

I planned an exit through the infamous ‘NADECO route’, involving an irregular border crossing into Benin, followed by a roadtrip to the nearest country that offers some measure of security as well as being English-speaking. Only one country fit that description - Ghana. Slowly I started actualising my exit plan. I left everything B.I.C. paid me that month - $1,850 - in my USDT wallet. I began slowly withdrawing the naira from my Zenith Bank account in stages, so as not to attract attention at a time when Godwin Emefiele’s CBN was handing out account restrictions to protesters like candy.

My girlfriend came visiting from Ebonyi and I took her out to Rufus & Bee, where I took great pains to make everything look normal. On November 4 the following day, she helped me move my stuff out of TPDC Estate. I gave it all to her and kept only my documents and a backpack with my electronic devices and one change of clothes inside it. We spent one last night together at an Airbnb in Ikeja, then it was go-time for me - after a 1-night detour for one last unit of extra-relationship coitus with another regular link.

I did book the Airbnb for 2 nights after all.

Not that it mattered anyway, because I would never see said girlfriend again, not that I knew it at the time. On the morning of the US presidential election on November 6, I left the Ikeja Airbnb with all I had - my backpack - and took an Uber to Victoria Island. I intentionally planned to withdraw the last N330,000 in my Zenith account via an OTC transaction on Adeola Odeku Street in case I was being monitored. The rationale was that there was no way on earth that someone planning to flee the country via Badagry would choose to announce himself on Victoria Island the morning of his great escape.

An attempt at misdirection

The lady teller at the counter recognised me, not as David Hundeyin the daredevil investigative journalist who might possibly be in trouble, but as “that guy from Twitter.” I was not sure how to feel about that. My next stop was at a Bureau de Change where the guy at the front desk somehow misheard “I want to change N330,000 to dollars” as “I want to change $330,000 to naira.” His lack of ears almost led to a Suspicious Transaction Report and a phone call to the EFCC, both of which I needed like a Fire Ant to the scrotum in that situation.

My last stop was at Saka Tinubu Street to meet Dr. Richard. I had only informed him that morning that I was leaving, and he insisted that I should stop by his office. I thought about the fact that the report we had worked on together had only 12 printed copies in existence - one of which had been immediately returned by a lawyer he shared it with, alongside a question along the lines of “Are you trying to get me killed?” I thought about the fact that I had one of said copies crammed into my backpack as I planned to embark on an irregular journey across 3 closed West African land borders.

Dr Richard would definitely not have approved of taking such a risk, but I didn’t tell him. I only told him I was leaving Nigeria that day. He bade me Godspeed and pressed $500 into my palm as I bade him farewell. I booked my Uber from VI to Mile 2, wondering if I would ever see him again, or if I would someday get to meet Dr. Obadiah Mailafia who also worked on the same report.

As it turned out, the answer to the second question was no. 5 months after I eventually made this report public in April 2021, Dr. Mailafia died in September 2021 under unclear circumstances shortly after honouring an invitation by the DSS. Shortly after he died, a rumour was floated in the Nigerian media that he died of COVID-19 - something his widow vehemently denied. Whatever “brief illness” he was said to have died from, bore a striking resemblance to similar “brief illnesses” that tended to spontaneously afflict individuals designated as enemies of state after visiting climate-controlled Nigerian state intelligence facilities.

RIP Dr. Obadiah Mailafia.

My Uber took a silly route and ended up inside Surulere, across the highway from Mile 2. I had to cross the pedestrian bridge across Oshodi-Isolo Expressway and get an Okada to Mile 2 bus stop proper, where I could find vehicles heading to the border. I chartered one for N16,000 and we set off across the disastrously bad Lagos-Badagry Expressway. When we eventually arrived - 4 hours later - I was informed that there was a semi-official system in place to manage the irregular border crossings and keep everyone happy. The Immigration officers had an arrangement with the Hausa Okada riders who took people across the border, and it cost N3,000 per crossing.

During my crossing, the Immigration official demanded N5,000 instead of N3,000 and all hell broke loose. My Okada guy - for some unknown reason - decided that he needed to protect my honour because the official was apparently trying to cheat me. I tried to let him know that I was not complaining, but this man was NOT having it. After nearly coming to blows with the rider, the Immigration official grabbed my backpack, told me to come down and said I would go to his office where he would search me.

In his mind, I was probably a Yahoo Boy on the way back to my base in Cotonou, and he could extort money from me by threatening to seize the laptop he was certain he would find inside my bag. In my mind, I was contemplating not one, but two laptops with Windows welcome screens clearly announcing: “Welcome David Hundeyin!” Not to mention the Silent Slaughter report (which later got Nigeria designated by Mike Pompeo as a Country of Particular Concern), casually sitting somewhere under the laptops. I could almost touch the cold, damp underground cells of Uncle Biodun’s DSS threat.

Somehow, I maintained my poker face and asked the official how much he wanted. He demanded N10,000. I counted 20 pink N500 notes into his hands and full-on barked at the Okada guy to get me out of there before he changed his mind. Once on the Beninois side of the border, I changed the last few naira notes with me to CFA and immediately got into a car heading to Hilacondji. This turned out to be the toughest crossing of all. Everyone had to come down on foot and execute a 20-minute endurance trek across deep beach sand, with ferocious mosquitoes attacking any exposed skin. All of this with a heavy backpack on, remember.

Once on the Togolese side, a new car had to be chartered to the Ghanaian border and as I was informed during one of the multiple Gendarmes stops enroute Aflao, any sight of a laptop in the possession of a Nigerian man could mean anything from severe extortion to jail time. Though small and cute and picturesque I was reminded, Togo was still very much a banana republic that had been run by the same family dynasty since 1958.

Crazy things happen in places like Togo.

Somehow, my 2 laptops survived the stop-and-search ordeal and soon we found ourselves at Aflao. Crossing over was a fairly straightforward affair, and as soon as I was on Ghanaian soil, something about the texture of the air seemed to change for me. For the first time in weeks, I felt safe. Also for the first time since leaving Ikeja that morning, I did not feel like someone was trying to take advantage of me. A front row seat from Aflao to Accra cost me only 30 cedis (roughly $2.50 in 2023 money).

I bought a SIM card at the border so I could have internet access, and it came in handy on the way when the driver played a song that my dad used to play back in the 90s and early 2000s while making the exact same roadtrip from Lagos to Accra, albeit under very different circumstances. Intense waves of nostalgia crashed over me as the vehicle raced toward Accra on this familiar road while the singer warbled over the sound system:

“Aunty Araba buro...Araba

Aunty Araba buro...Araba…”

Shazam informed me that the song was called “Araba” by a Ghanaian Hiplife artist called Naa Agyeman.

Amidst the rush of nostalgia, I suddenly felt my eyes glassing up. The most recent time I had been on that road was in 2010 during a family vacation with my dad, 2 sisters and mom. Despite the complicated family situation, it had still been very much an enjoyable West African family getaway, and yet here I was exactly 10 years later with nobody and nothing.

In the intervening period, my siblings and I had drifted apart and now led completely separate, non-intersecting lives across multiple continents; dad had died, and my mom, well I suppose she was alive technically, but she was as dead as a doorknob to me. This road, which evoked some of my most treasured childhood memories of road tripping across West Africa, was now the scene of my lone escape from what used to be home, armed with nothing but a backpack. I placed my head between my arms and sank my face into my backpack as though I were taking a nap, but I forgot to take my glasses off first.

When the song ended and I raised my head, the lenses had water on them.

After about 4 hours on the road, the bright lights of Accra started to come into view. I glanced at the Villagio - the famous landmark building at Dzorwulu which yells “Accra!” louder than the Eiffel Towers yells “Baguette!” I tried not to think about the fact that just 9 months before, I had flown in here with my girlfriend for an intimate weekend getaway. Now, I had left her in Nigeria and crawled here across land borders like a rat, hoping to make sense of a new post-massacre reality that had started barely 2 weeks before. I took a taxi from Dzorwulu to my Airbnb in Kasoa.

At the time, I had no idea that Kasoa is located in “Accra” the same way Doha is located in the UAE. Not for the last time, I would learn that pinching pennies as a foreigner was not the way to go in a country like Ghana. The place itself turned out to be a bit of a dump, located at the bottom of a ravine where even 2G internet signals could not penetrate. I had booked an entire house because in the post-massacre period, William had made many noises about leaving Nigeria and moving to Ghana alongside me. William - not for the last time it turned out - had significantly more bark than bite when it came to making key decisions. It quickly became clear that he would be a no-show, and renting a whole house was superfluous.

After 2 very uncomfortable nights, I eventually found a tiny studio apartment in a city centre neighbourhood called Adabraka. Here, I started the process of building what - unknown to me - was going to be my permanent new life as a Nigerian in exile. I had initially made no real plan beyond leaving Nigeria and putting my head down in Ghana for a few weeks. Those few weeks went by quickly. I witnessed the marvel of Ghanaian elections on December 7, where an exercise to elect or reelect a president went by smoothly like it was a public holiday. In fact, it was when I went out to buy food in the evening that I realised that there was a polling booth right outside my building. Not a single gunshot. Not a single scuffle. No “late arrival of materials.” Just mature, rational Africans acting like the adults they were.

I remember feeling distinctly ashamed.

Between November and December 2020, several Nigerian journalists, activists and civil society figures quietly found their way into Ghana and other surrounding countries as the Buhari regime decided to flex its muscles on the people it loved flexing on the most - those who couldn’t hit back. My lonely outpost in Accra soon swelled into a group of 3 as first Ndi, then Ralph joined me in quick succession. While Ndi was always upfront about the fact that she had not decided what to do next, Ralph and I - merely a few weeks separated from our antics in Maitama - were quickly forced to face the realisation that we might in fact never go home.

One evening in early December, Ralph and I were sat on the deck chairs on Ndi’s balcony at Pine Courts Apartments surveying the “ruins” of the lives we both had just a few weeks before. At the time, we were coordinating a #FreeImoleayo Twitter campaign to pressure the DSS into releasing Imoleayo Michael, a computer programmer who was arrested for protesting and detained for 41 days. Apart from Yele Sowore who availed us the use of Sahara Reporters to promote the campaign, it had become very clear to us that many people who had been eager to place their faces next to the #EndSARS brand - without actually doing any of the dirty work during or after the event - had achieved their goal.

Money had been made. Headlines had been written. NGO funding proposals had been written and approved. Faces had appeared on the front pages of international media. Those of us who actually got involved for purely ideological reasons suddenly found ourselves alone, trying to get protesters out of prison while ourselves struggling to tread water.

We made a promise to each other that evening - that going forward, the only condition on which we would agree to set ourselves on fire for people ever again, was if said people were ready to set themselves on fire too. “We will not die for people who are not willing to die for themselves,” was the exact wording of the vow we made. At the end of the day, the expenses, the stress, the trauma - everything that came with trying to be strong for other people - had been left entirely for us to figure out individually. Especially the trauma and anxiety that came with the territory.

On December 30, both of us realised just how traumatised we were when we visited Labadi Beach to hang out. There was a lady selling food next to one of the beachhouses, and we decided to get some jollof and chicken. The lady had a little daughter who couldn’t have been more than 4 years old. While waiting for our food a little distance away from them, we spotted 2 Ghanaian policemen walking up the beach toward us, dressed in black and holding AK-47s, just like their Nigerian counterparts. Ralph and I beckoned at the little girl who was playing near us, telling her to see who was coming. Instinctively, based on our Nigerian conditioning, we felt a need to warn the innocent little soul that danger was coming and she should run to her mom for protection.

Instead, the little girl looked up, saw the policemen, and started skipping toward them, utterly unafraid and screeching in delight with her full set of milk teeth showing, “PO-YEES! PO-YEES! PO-YESS!” The policemen on their part, calmly acknowledged her, returned her smile and even stopped to play with her for a few moments before continuing on their way. Not a single word was said at that moment, but when Ralph and I looked at each other with our mouths open in utter amazement, nothing needed to be said. It turned out that being mortally terrified of police to the point of using them to scare young children, was a uniquely Nigerian experience - one that we were both completely, hopelessly and maybe permanently marinated in.

Apparently for everyone else, the world was a less terrible place.

It wasn’t that the world outside was that much better than Nigeria.

But it was that much less terrible.

*************************************************************************************************************

‘Breaking Point: A Journalist’s Quest For Salvation In Nigeria’s Chaos’ was nominated in September for the 2025 ANA Prize for Non-Fiction. In March, it was listed at number 17 on the Roving Heights/Open Country Mag 2024 Bestseller List. You can buy a copy from the following distributors:

Roving Heights (Nigeria): https://rhbooks.com.ng/product/breaking-point/

Amazon (International): https://www.amazon.com/Breaking-Point-Journalists-Salvation-Nigerias/dp/B0D6428PFW

Amazon Kindle (Soft Copy): https://www.amazon.com/Breaking-Point-Jounalists-Salvation-Nigeria-ebook/dp/B0CX21GMHN

Nuria Bookstore (Kenya): https://nuriakenya.com/product/breaking-point-a-journalist-quest-for-salvation-in-nigerias-chaos/

Midland Books (India): https://www.midlandbookshop.com/en/product/breaking-point

Wow!

I took my time to read every single line and I must confess that I was so emotional reading this.

David God bless you, I've been a kin follower and I love your work.

The killing and the inhumane melted at us at the Lekki Tollgate is still very fresh in our memories.

It's so sad the kind of evils that govern Nigeria.

I believe though it will take longer than presumed but everything will be alright.

Keep it up Dave 💯

20.10.20 remains a day in Nigerian political and social history to never forget. It was a chance to regain freedom which many Nigerians didn't even know but were devoted to.

Your struggle for Nigeria sir Dave can't be undermined. It takes patriotism, love and courage to do that. Whatever ways, Nigeria's can't forget what you do for them; the voice you lend and the delight you sacrifice for us.

While I remain a fan of your work and above all a beneficiary of the knowledge you pass, I urge you to remain strong and still committed to your ideologies.

It is only delayed but can never be denied. You're a lion 🤝🙌